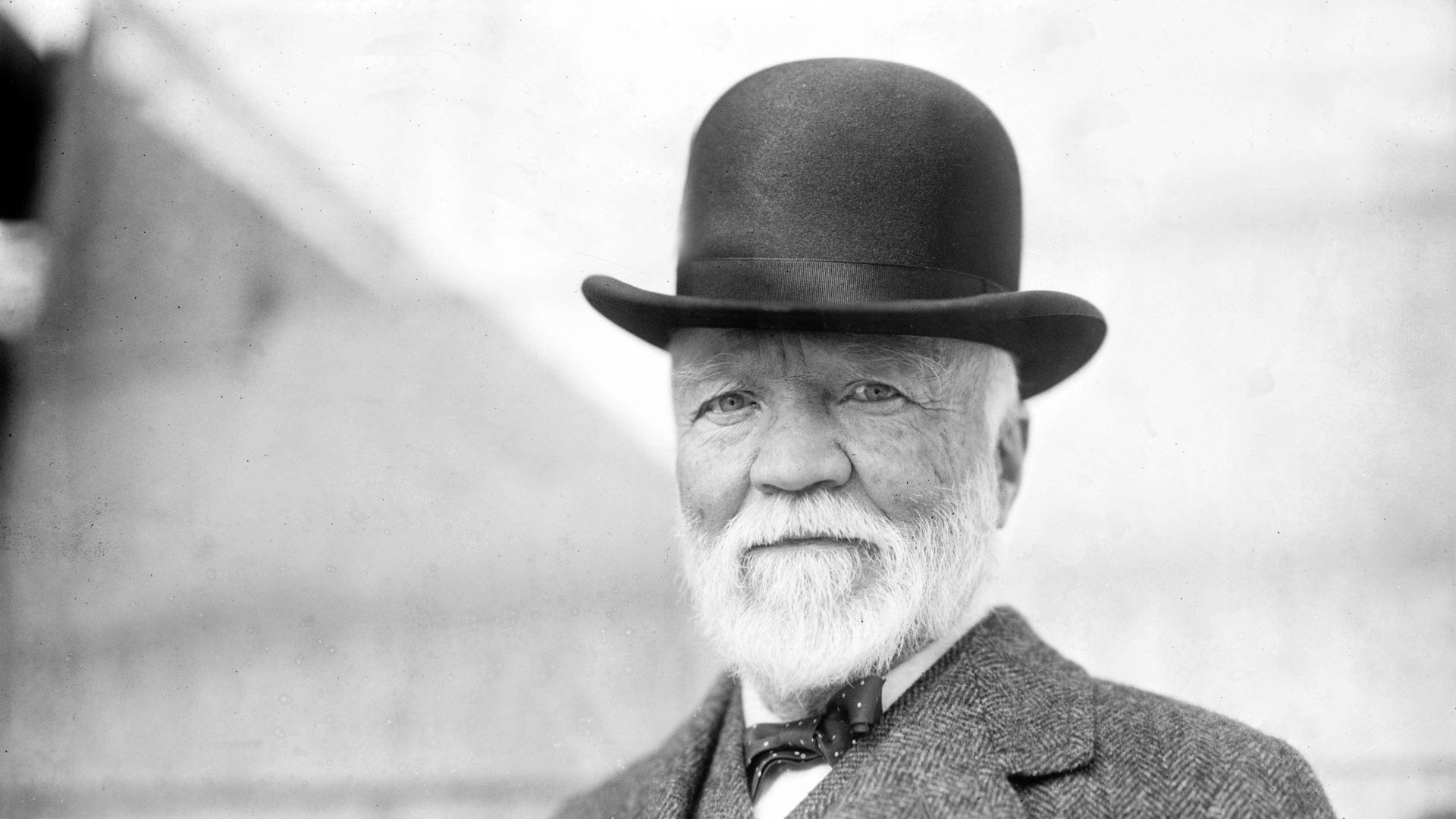

When Andrew Carnegie sold his steel empire for $480 million in 1901, the news travelled like thunder. It was the largest business transaction ever recorded — the kind of event that usually becomes the centre of a life story. Yet for Carnegie, it seemed almost beside the point. There was something faintly mischievous about a man who built one of the most formidable industrial machines on earth and then spent the rest of his life dismantling his claim on the proceeds.

Carnegie grew up far from the world of steel mills and capital markets. He never viewed the accumulation of wealth as the final goal. Wealth, in his mind, was a stewardship — a temporary responsibility entrusted to those who could use it for the broader good.

His philosophy, crystallised in his 1889 essay The Gospel of Wealth, sits at the heart of why Carnegie remains such a compelling figure for modern investors. He argued that wealth should never be hoarded, nor distributed indiscriminately, but deployed purposefully: “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.”